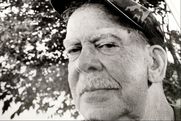

One of three sons, my grandpa was raised during the Depression in rural Illinois, learning to make the most of what you had available and foraging and hunting for the rest. He was taught about living off the land from his father, a gruff brawler that I never met, who lived alone on a white dirt farm outside one of the many one-horse towns in our area. Grandpa was the best fisherman I knew, and hunted for small game and dove between hours devoted to his garden and family. However, that small window in mid-spring where temperatures and precipitation hit "just right" sent him to the timber with his walking stick, faded hat cocked ever so slightly, suspenders fighting mightily against gravity, and a purple mesh potato sack stuffed in his back pocket. Better for spreading the spores from picked mushrooms, you know.

Over the past few years, mushrooming on my family farm has been less than stellar. It seems that the morels started to leave when grandpa passed, and all our secret spots have left us empty handed, year after year. We can blame some of the problem on the cattle grazing heavily in the timber, some on uncooperative rains, some on global warming, bad juju, or Russian fungus espionage. Whatever the reason, our dead elms bore no fruit this year, or last, or the year before last. To find morels, I had to leave home.

One text with a glorious mess of mushrooms spread on a kitchen counter led me to invite myself to my buddy's property...thank heavens I have good friends that put up with my boundary issues. We spent an afternoon with rubber boots and plastic sacks walking up and down a sandy creek bed lined with chestnut saplings and clumps of multiflora rose. I had grown accustomed to mushrooming that was far more walking than picking; you know the kind, and I was prepared for more of the same, using mushrooming as an excuse to spend some time outside. Oh, how wrong I was. I think I found my first morel within the first three minutes, less time than it takes to cook a potato in the microwave. It happened just that fast.

It seemed that everywhere we looked, we found mushrooms. I even shimmied down a precarious bank to pluck a monster growing at the root of a tree exposed by the creek below. We were right in the sweet spot of the season where the small greys had passed but the giant yellows had yet to come, leaving us with a mess of meaty mushrooms ripe for the picking. We stuffed our sack quickly, and found ourselves filling hats and pockets as we separated to comb different areas. Inevitably, one of us would abandon our post because the other came into a fresh bounty. It was as if Mother Nature had designed the best adult Easter egg hunt, and I filled my basket with the enthusiasm of a child.

The day's end found me two pounds richer, the only time a woman is happy to have more weight than less at her disposal. Although it was late when I got home, I took the time to carefully clean, slice, and soak my mushrooms just as I remember doing as a kid. The next day, like a dutiful daughter, I brought my mushies home to my parents, and we devoured half of them in the blink of an eye, dredged in flour, fried golden-brown, and accompanied by a cold beer, per tradition. As I chewed on the last morsel, I contemplated what my grandpa would have thought of the pile--if his keen eye would have found more that I passed by, if he would have fallen in the creek and come back to the house, soaking wet but with a potato sack full to bursting. It's funny how a mushroom can be so tied to a memory, fleeting but familiar, like the intangible scent of morels on the warm spring breeze.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed